|

No Redemption Keith Pattison – David Peace ISBN 978-1-906601-20-1

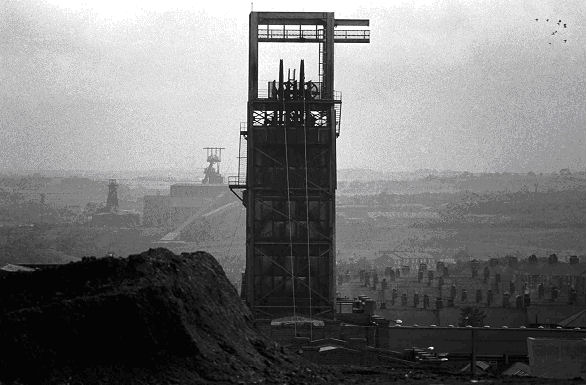

“We were fortunate that during the strike we had Keith, our photographer. Because Alan Cummings The limitation of words is soon encountered when trying to convey the power of this quite remarkable pictorial collection of scenes from Easington Colliery during that historically dramatic year. Easington even without the strike was boldly typical of the Sunderland coastal pits. Huge winding towers dominating the blackened landscapes in all directions, the grey industrial mass of tips, chimneys, and surface structures. On the skyline, stark and perhaps a little foreboding the headgear of Easington, Hordon and Blackhall Collieries, dominating the teaming ranks of pit houses and dense communities like steel castles overlooking their subjects. These places were built and exist for one reason, to mine coal. Almost every living soul in this coastal strip is fed clothed and housed on its industry. The pit dominates all aspects of life, labour, love and death.

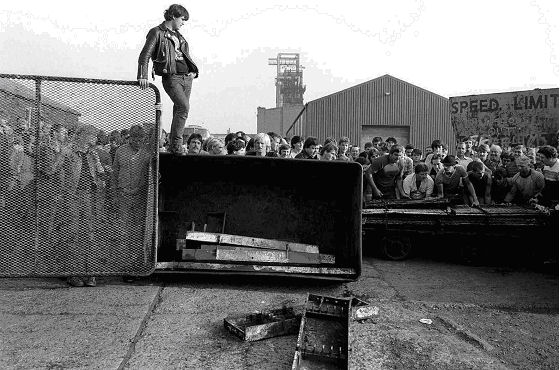

David Peace provides the brief commentary and as it turned out the books title and that of the exhibition of full size photographs which have graced London galleries until recently “The strike ended with the defeat of organized labour and the defeat of socialism. It was a victory for Thatcher’s idea that there was no society. Now its carte blanche, full on, privatisation, deregulation, trickle down. Much as I admire Billy Elliot and anything which makes people aware of the strike, at the end of the day I’m not satisfied with nostalgia. I didn’t want the book to offer a sense of redemption because as a country we haven’t got it. And we don’t deserve it.” There are few words in this book, in many ways perhaps enough words have been spoken on the strike, not all of them useful or accurate, but the adage ‘every picture tells a thousand stories’ is certainly true here and to a great extent they speak for themselves and offer a truth beyond argument. Those few words there are are marshaled by David Peace (author of the deeply dark and troubling fact based fiction GB84) in a reflective 25 years on and incidentally on the eve of the 2010 election. Alan Cummings, former Easington Lodge Secretary and Area EC member, Jimmy Johnson and his wife Marilyn twelve month activists pickets and kitchen organizer. They ponder their memories, these photos and what that all meant and perhaps still means. Jimmy explains that the Durham Area hadn’t in fact voted to take strike action, and only did so in solidarity with Yorkshire and Scotland and that only on the casting vote of the area chair, but once out, they stayed out, in villages like Easington firm and solid. Alan is one of the officials who still feel aggrieved at the lack of a national ballot “I was at that meeting in Sheffield when they brought it (the positive ‘yes’ vote requirement) down from 65/35 because before then 65 had to go for a strike- but they brought it down to 50/50 (actually 50% plus 1). And I said, Great. We’ll have a ballot now. And get it easy. We’ve got 50 percent. But we never had a ballot, I can’t understand why.” The truth is , all the evidence is that we would indeed have won a national ballot, the NCB under MacGreggor commissioned two NOP’s and both confirmed the strike vote taken in the heat of an already rolling strike ballot would be successful. Jimmy’s words shouldn’t be taken too literally of course, he knows the reason how at least we didn’t have the ballot, because the conference after seven exhaustive proposals and mass pit head meetings voted simply not to and to call instead on all miners to respect picket lines. Why that was, Jimmy knows too, but perhaps still doesn’t agree with that rationale. The issue remains vexed in any discussion of the strike, but these pictures and this story demonstrate it was the strike and solidarity and community cohesion in the teeth of every sort of brutality and deprivation which was decisive here and not the means of its arrival. “We had a very young workforce. I mean the average age at our pit must have been 34 years. Didn’t have many people at the pit who were over 55. By virtue of the redundancy scheme. And so the strike was solid. And traditionally our pit has a name that goes back to the 1920s as a really militant pit. So men were really good. And the women. That was key and all. Because if women wanted her man back, I think the man went.” Alan Really that statement reflects the key focus of this book. Of 180/ 190,000 men on strike, the greatest every number of pickets we managed to mobilize was 25,000 at Orgreave. This means 155,000 strikers never picketed, and yet remained loyal to the strike. That they were able to do so was without the slightest doubt due to the women’s support groups and the solidarity groups around the world who held the fabric and moral of these villages together. Fed the families, organized the holidays and day trips away from the heavy imposing presence of the occupying police force, organized the parties and hardship funds under the sullen gaze of the welfare agencies following instructions to starve the miner’s families back to work. The toughest battle for the miners and their families was not on the picket line, or in that field at Orgreave, but back within the four walls of the family home as it is slowly depleted of furniture and possessions, coming in from the incessant rain and snow wet and demoralized to an empty hearth and cold damp house. Hungry children, despondent teenage family members. That battle field is well recorded here, the First World War trench of the strike. There are many close studies of people’s faces in this book, deep enquiring, searching photos. Intense, lost in thought and mental conflict.. Photos of men on the cobbles, in idle groups, passing time. The intensity of the picket line, the sheer raw anger at the audacity of scabs so wretched and shallow they break that link, that bond of solidarity and loyalty, in a social betrayal so deeply felt the whole community reacts in a huge collective surge of repudiation.

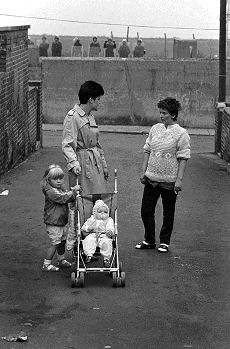

The police enter these scenes, these alien and hostile streets as total outsiders, strange and at odds with everything around them, they look lost. They are unwanted, they do not belong here, they are the hostile occupation troops in a foreign country, they have neither the language nor the culture. They march, besieged on all sides by people standing on their own streets and looking from their own windows, just looking. In scenes reminiscent of occupied Belfast or Derry, the town goes about its business as the army of police stake out shops and street corners, fields and backlanes. The armoured transits push through crowds sullen and unwilling to move. One is reminded of the cops in Harlem ordering the black crowds ‘go home’ and they responding, ‘we are home’. For crowds of old pit lads and their wives it is a revisitation from their youth in the 20s, the same scenes the same bitterness, the same struggle.

Mass crowds in triumph and confidence cheer an explosive Arthur Scargill animated at the podium of the welfare club, heartbreaking shots of anxious looking exhausted children queuing for their meal.

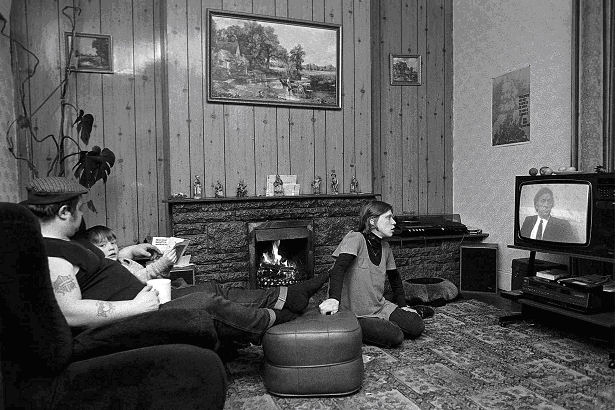

A living room fireside scene, on Telly Arthur Scargill watched by the teenager, the child the Dad on his couch, on the walls a picture of Karl Marx, and a Constable. In scenes which could be interchangeable with the 20s, or the 1890s gangs of cops mount shotgun on solitary scabs, escorted through the back lanes, their heads bowed, their sin buried like their hands deep in their pockets, watched by betrayed children and their mothers from their doorsteps. An old lady in her headscarf walking with a stick passes the line of helmeted aliens her facial resentment as evident as had she been carrying a placard bearing the words ‘contempt’. The icy blasts of winters snow, and despite the long expected word that ‘General Winter was marching into this battle’ it was now not certain whose side he was on. The desperate scrabble for coal from abandoned pit tips, from the beaches and the raging sea, anything to keep some cheer in the hearth and hot water at least enough once a day for a bath. This book is a testimony and a monument I think beyond anything so far produced it will stand forever in tribute to these coastal villages and the resilience of its population. 2,500 men worked at Easington by the last day 54 had gone back, and 32 of them went in the last two weeks of the strike broken and dispirited with no sense of direction or hope. It was that knowledge that we were now making scabs of good men, that finally decided to end it together and march back together. “There were a lot of issues leading up to the end of the strike. I had a good hard working committee. We were picketing every day. We had a feel for what was happening. I kept a close watch on the numbers that were returning back to work. And the trend, it was a trickle, but there was a percentage increase…it was heartbreaking for the lads to see them bloody busses going in. So I had meetings with the left…There’s no light at the end of the tunnel. You’ve got to give somebody some kind of hope. Lights out we’ve got a chance. No light out, no chance. And I said…who brought them out? We brought them out. And its we who should take them back….”

The final shot in the book is the mass lodge meeting voting to return to work with a forest of hands held erect, there are few smiles and cheers. Relief perhaps in this instance, within ten years it was all gone, just the ghosts and the memories remain, though now too we have this book and a growing feeling that we as a class have been pushed as far as we will go and it is time to be bold and brave again.

Keith Pattison: NO REDEMPTION

|