Coal was our life

In the 1950’s a book regarded as a classic Coal Is Our Life, focused a tight study on a pit town in West Yorkshire, the folk, their aspirations their lives. In this book Royce Turner returns to the same locations now and confronts us with a devastating contrast.

This is a book that needed writing, it says things which desperately needed to be said, and in a style which is polemical, confrontational even. It is as if the book has erupted from the suffocating swamp of PR sociology which has buried the decimated pit villages since the mass closure programmes. The book challenges the self congratulationary business schemes, job creation schemes, retraining schemes, coalfield regeneration, reinvestment, reinvention schemes which everywhere tell us they are at work, which everywhere publish reports and surveys, seem to be the biggest employment growth area themselves though not of course for the pitmen or their families, yet still the deprivation and poverty and wretched loss remains. How can so many organisations, awash with European and Lottery money be running so fast and yet standing still ?

Talking of housing in Featherstone in 1996 :-

"The families that lived in them were beset by social and economic problems. On top of that the residents were struggling to survive in the face of a poor local reputation. It is almost as if the houses are a physical representation of hopes dashed, of a vision for the future turned sour. People had secure employment, brand new modern houses, what were seen as good prospects for their kids. Now forty odd years later, the houses are crumbling, and the lives have crumbled too. Old battered cars sit on oil-soaked drives. If its sunny people sit on the door step for half a day. There's nothing much else to do."

And Maltby:-

"It was in one of the worst states of disrepair that I have ever seen any housing. Sean (a local councillor) told me that it had improved a lot from what it had been. Many houses were boarded up and dropping to pieces. Some of the youngsters had taken to breaking the gas pipes inside and throwing petrol bombs in. They’d completely lost a few houses this way. It provided the youngsters with a bit of fun. Sean took me to the derelict houses that had been occupied by his family and friends, where they had looked after the gardens and been good neighbours and helped each other out. The gardens are in rack and ruin, gardens like jungles, without the eerie charm of a jungle. A few yards away is the footpath next to a railway line where the smack dealer had threatened to kill Sean for trying to fight the drug trade."

The book points to areas none of the incoming social missionary folk can comprehend, they never understood what it was we had in pit communities in the first place, how the hell can they understand what it is we have lost. Even for those of us living in the shadow of the former coal industry as it struggles to survive and maintain a living and a tradition, cannot often explain what is lost, though its loss is massive, it is more than the sum of any parts, roots, job, pride, class identity ,community, culture, ethnicity, politics, vision,

you chose to add together. Certainly grim, toil, death, injury, disease, conservatism, are also words and concepts which battle with the former as descriptors of pit life, no one here is looking for any nostalgic glow. The cold light of most poverty strewn, heroine addicted, crime ridden pit villages would quickly damped any of that. Yet the change is real, the contrast inescapable, the loss of real life values , and the will and determination to intervene and fight back, is everywhere visible.

" In Featherstone there arnt many choices. If you get chance of a job at the packaging factory you take it. You think yourself lucky to receive what you see as decent money and a gold watch and to get an invitation to a dinner and dance at Christmas."

"The pop factory represented the only foreign investment in Featherstone. Yet foreign investment we were told throughout the 1980s as deindustrialization savaged large parts of the economy was going to be the salvation of local economies. Looking at a small town like this gets you away from the platitudes and generalisations of national politicians who wouldn't even know where Featherstone is except when its needed to provide a rock solid labour seat for some anointed rising star....

Yet these were the two themes of the 1980s and much of the 1990s. A newly rejuvenated small business sector, and inward investment by multinationals were going to transform the economy. Neither has happened in Featherstone, and neither will."

But the author is sucked down too deep by the depression and despair he sees all round him. He declares :- "You walk around, and you want to help them. You want an economic and a social and a cultural revolution. You want to remember them as they were, full of pride and hope for the future. You want them strong, and confident. Knowing that their day is to come, but come it will, as they used to believe. But you know it isn't and you know that you cant really do anything about it.....I remarked on this once to an older man who had lived in the locality all his life. He took his time before answering me, thinking about my words. Then he fixed me with his now watery but still steely blue eyes. "What do you expect them to do ?" He said. Riveting the position deep into my psyche. I suddenly realised of course, that I hadn't a clue."

"Public ownership as it might have become as we approached the millennium had never simply meant ‘Government Ownership’ in the coalfields, at least certainly not back in the Forties, when it first came in, or even in the Fifties. It may never have lived up to its promise, but it had been seen as being about much more than that. It was about power. About moving power from the despised coal barons to the workers.....

It is a spirit a culture a world that has passed. It was a fleeting moment in political history ; a moment in which it was thought that the collective could achieve more than the individual. It will never happen again. All that is believed in the 1990’s by ‘Labour’ and Conservative is that the successful entrepreneur is the ‘key player’ in the economy. There's nothing else. There are no grand ideas anymore. Nothing we can strive for, and be proud to call our own."

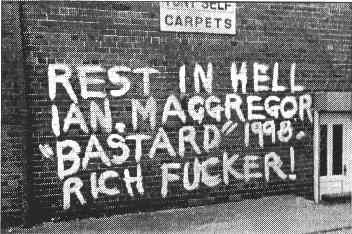

Royce would raise a cynical smile at the middle class socialist revolutionaries meeting in the local battered pub to bring about the revolution and perhaps given the depth of defeat and loss of confidence we could forgive him that. Yet class anger remains 13 years after the defeat of the miners strike in 85, MacGregor died. Someone felt enough to go to the site of a former Barnsley Colliery and paint in giant letters on the walls: Rest In Hell. Ian MacGregor. Bastard.1998. Rich Fucker !

Turn out to the Durham Miners Gala seven years since the last Durham Colliery closed and see the pride and class anger as the banners retake the streets carrying their old message of class struggle and Socialism. 50,000 turned out last July. As this review is being written the tiny NUM ballots once again for all out strike action. Class politics do still strike a chord in pit communities but it would be a downright lie to suggest most eyes had their vision fixed in that direction. The antisocial spread of emptiness consumes everything around it and one needs real determination not to succumb to it. We need a national fight back linking these isolated pit villages to struggles and issues nation-wide, we need surely a return of vision and hope, lying down and dying has never been our way of dealing with hardship.

The book is a classic, should be read, if I have any criticism other than the lack of hope it is the front cover which suggests nothing of the fire and power inside.

Coal Was Our Life is available from Sheffield University Press.Learning Centre, City Campus,Sheffield s1 1WB ( 0114 225 4702) Price £12.99 + £1 p&p.